Here's a proposition for you: Los Angeles is not sprawl.

OK, OK — I realize that sounds like a pitch for Slate, the online magazine with a reputation for publishing contrarian opinions for clicks. Los Angeles has become virtually synonymous with sprawl in the public mind for a number of documentable reasons, including extreme traffic congestion, poor air quality, and high housing prices. But it’s also the densest urbanized area in the United States, with nearly 7,000 people per square mile as of the 2010 U.S. Census. How can an urban area be so sprawling yet so compact at the same time?

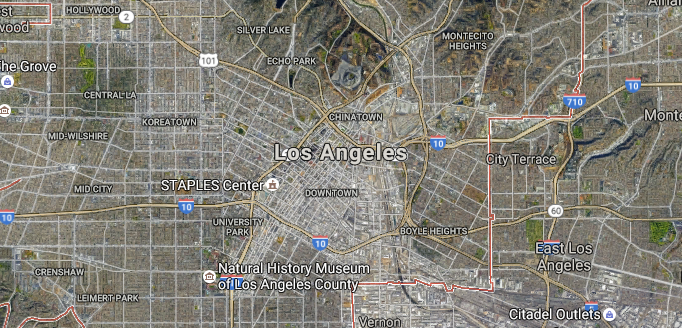

In his 2005 paper “The Worst of Both Worlds,” Eric Eidlin explores sprawl as a psychological concept, asserting that Los Angeles is an example of “dense sprawl.” Its greater urbanized area boasts all of the negative consequences of high population density, with none of the benefits that generally accompany such density, such as vibrant street life, tightly knit neighborhoods, and fast and efficient public transit (though this is gradually changing). Los Angeles is “compact” in the sense that it is laid out as a series of high-density suburbs, whose residents feel the negative effects of the city’s urban form in their daily lives much more directly and potently than in a “less compact” metropolitan region such as New York.

The point here is that measuring sprawl purely on the basis of density leaves out a number of factors that have important, direct impacts on residents’ quality of life. Scholarly literature on the measurement of sprawl has evolved considerably in recent decades to incorporate additional indicators, such as spatial continuity (whether developable land is organized in a continuous block), nuclearity (the degree to which a locality's jobs are located near the urban core), and proximity (how close jobs are to where people actually live).

Along these lines, for their 2006 paper “There Is No Sprawl Syndrome,” Jackie Cutsinger and George Galster performed a cluster analysis on U.S. urbanized areas and determined that U.S. sprawl falls into four very broad categories:

Los Angeles, perhaps the United States' most iconic example of sprawl, is a form of "dense sprawl" where a consistent density is maintained throughout the urbanized area. (Source: Google Maps)

1. Dense, deconcentrated

Examples: Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis

This category is the type of sprawl described earlier — intensively packed with buildings and infrastructure and absolutely filled with people, but with little variation in housing or job patterns across the broader area. It’s a gray, monotonous brand of sprawl where people are surrounded by other people at all times, but generally live very far from jobs and centers of activity. It’s the type of metropolis that influential planning theorist Le Corbusier would be proud of — lots and lots of city, but for many, it’s difficult to actually access the cultural amenities that actually make cities worth living in. It's like Coruscant from "Star Wars" — a planet-sized city that looks cool on the big screen, but would be miserable to actually live in.

Philadelphia is an example of "leapfrog" sprawl, where new development "leaps" over vacant land to the fringes of the urban area. (Source: Google Maps)

2. Leapfrog

Examples: Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Grand Rapids

Cities in the second category of sprawl feature development patterns that “leap” to the periphery of the urban area, with development frequently cropping up in far-flung reaches, often surrounded by large swaths of vacant land. From the air, it’s the type of sprawl that probably looks the most like “sprawl” to the naked eye, with patches of development that extend from the urban core like the arms of an octopus. In leapfrog urban areas, jobs are often clustered together in dense patches, but much like in the first category, they are generally very far from where people actually live, resulting in an inefficient excess of vehicle miles traveled.

New Orleans is a city with a dominant core of businesses and residences, with the "sprawl" emanating from the fringes of the urban boundaries. (Source: Google Maps)

3. Compact, core-dominant

Examples: Las Vegas, New Orleans, Fresno, Washington, D.C.

The third category of sprawl features cities with one dense, dominant metro core that then emanates out in all directions. Examples from the list above include the Las Vegas strip, New Orleans’ French Quarter, and the urban area surrounding D.C.’s National Mall — basically, cities with One Really Famous Area, and a bunch of other stuff. Within this core, jobs and housing are generally located close to one another, but the urban areas are much less dense overall than those in the other three categories, and the mixture of land uses is generally very scattered on the broadest scale, suggesting an inefficient, ad hoc, “checkerboard” pattern to development in these areas.

Baltimore does not hit any extreme in the sprawl indicators used in Jackie Cutsinger and George Galster's 2006 study, but would still be considered "sprawling" by many residents, which speaks to the power of sprawl as a psychological phenomenon. (Source: Google Maps)

4. Dispersed

Examples: Baltimore, Cincinnati, Houston, Milwaukee, Seattle, Salt Lake City

This category of sprawl can be dubbed “jack of all trades, master of none,” because it does not represent an extreme in any particular measure of sprawl. This makes it possibly the most fascinating category, not just because it is by far the category that describes the most U.S. urbanized areas (on average, twice as many as the other three), but also because the fact that it is not “technically” sprawl by any one measure is a testament to sprawl’s psychological nature — the “I know it when I see it” factor. Sprawl is like the Voldemort of urban planning: its name means trouble, but it comes in so many forms that it’s tough to define and even tougher to fight.