introduction

Rapid industrialization and urbanization are causing severe environmental and health crises in Mongolia’s cities, especially in Ulaanbaatar, the capital and most densely populated city in Mongolia. Along the Tuul River, on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, a little girl is crying, and her mother is silently facing her heart disorder diagnosis. In the Ger districts of Ulaanbaatar, many low-income families face the same tragedy. But still, more and more nomadic Mongols are migrating into the city to seek job opportunities and praying to their sacred river – Hatan Tuul – for a prosperous life. Unfortunately, the beautiful river that fuels the rapid growth of Mongolia is now filled with consumption wastes and pollutants, smelling of raw sewage for miles. The lush steppes were replaced by mining pits and transporting roads. The nomads who used to herd on the vast grassland are now crowded on the edge of Ulaanbaatar: struggling with unemployment, limited access to resources, and a polluted environment. Children -the youngest and weakest group - are most vulnerable to the impacts of the severe environmental crisis. Their families become victims of mineral resource exploitation and the prioritization of the global economic market.

Image 01: Drawing of the Ger Districts in Ulaanbaatar. Self-Creation.

“Song of the Chi Le”

The Chi Le plain out spreads by

Where the Great Greenery Mountain does lie.

Like a woolen ten hangs the sky,

Covering the wilderness from on high.

Boundless, the sky is so blue;

The Wilderness seems boundless, too.

Rippling through the pastures, north winds blow;

The grass bends low,

The cattle and sheep, to show.

The Growth of the Ger Districts

This Chinese poetry-song, which has been told and sung for over 1500 years, describes the tale of the nomadic herders living freely on the beautiful northern prairie. Even nowadays, when people mention the Mongolia region, the first image associated would be the lush steppes, incessant mountains, and nomads riding with their livestock on the endless grassland. However, the reality is that this land is mainly covered by sand because of the severe desertification in this territory. 77 percent of the territory and almost 90 percent of its pastureland is threatened by desertification and land degradation.[3] When the global market found the “true treasure” - abundant mineral resources underneath this nomadic land, the land that created one of the most unique cultures in the world was then transformed into the battlefield of resource exploitation. Capitalism hit this fragile desert-steppe ecosystem, and families who have been living on this grassland for generations became the sufferers of the global economy.

The culture of Mongolia has been shaped by its nomadic way of living. For millennia, Mongolian herders have been grazing their livestock from place to place on the lush steppes. They relocate their houses – Gers – from place to place depending on where they are herding. In the Gobi Desert – a place is known for its extreme weather – herders with generations of passed-down wisdom have learned how to live on this harsh but thriving land. They are acquainted with reading and predicting the weather, identifying and harvesting wild plants for food and medicine, maintaining and respecting the relationship between nature and humans. For generations, their sense of belonging has become deeply connected to the land they are living on. Their life and stories were not connected to properties, but rather the land that they shared with pasture and many other species.

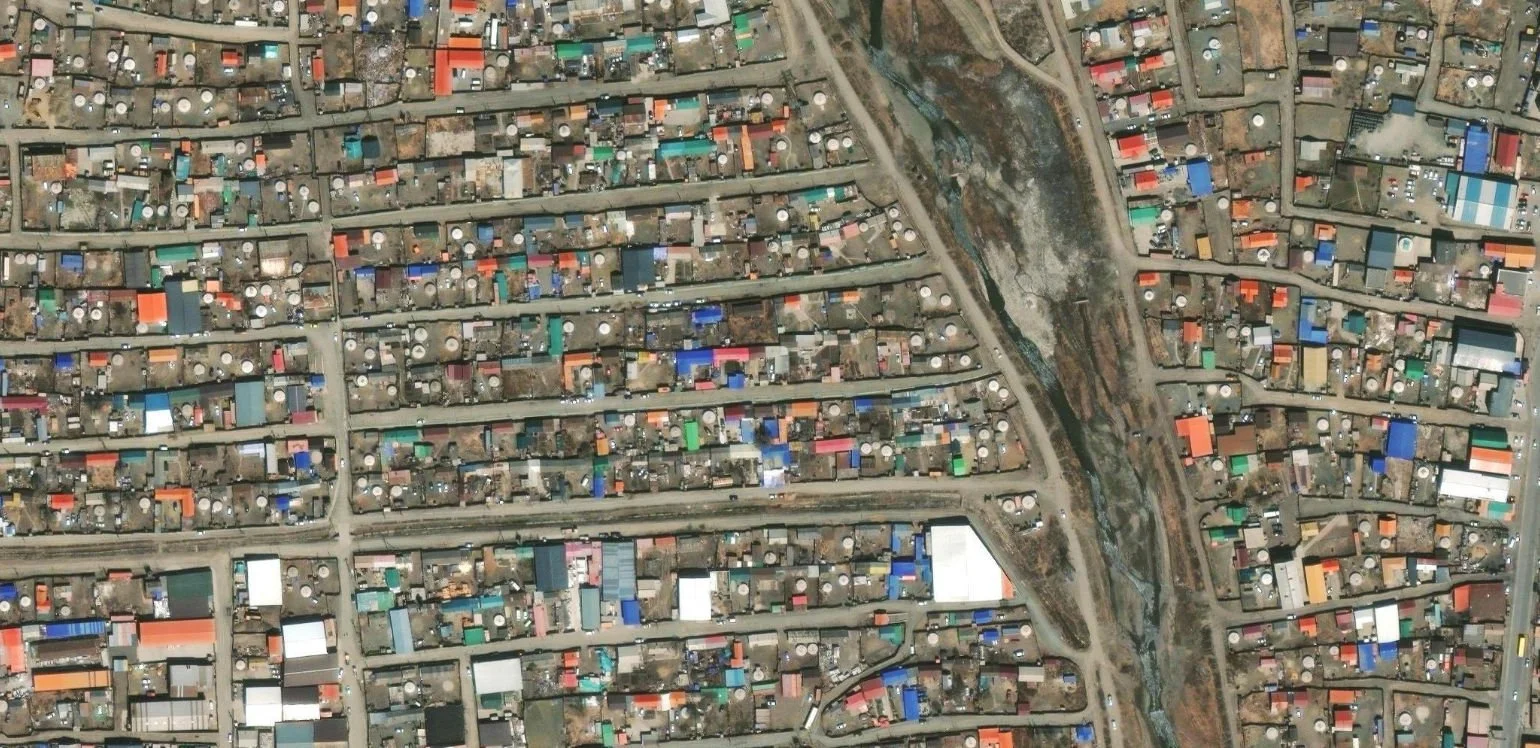

However, this nomadic lifestyle is challenged by the growth of capitalism, industrialization, and the global economy. “In 1960, almost two-thirds of Mongolia’s population lived in the countryside.” “Today, that number is less than one-third. A large portion of them is nomadic herders who have migrated to the capital, Ulaanbaatar, to make a different kind of living.”[1] From living and traveling on boundless grassland to now settling down at the edge of the city. In this urban migration, herders have to give up their nomadic lifestyle to adapt to the urban landscape and the concept of land property. Migrating to cities and facing conditions they are not familiar with, many Mongols are adapting urban lifestyle by introducing the traditional dwelling form - Ger - into the city. Then we see Gers at the edge of Ulaanbaatar (Image 02). On the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, many migrants start their city lives without housing, sufficient utilities, and infrastructure resources, forced to suffer polluted air, soil, and water. They settled the traditional portable Gers within the city because of the unaffordable housing prices caused by overpopulation.[4] They burn up coals or wood to survive the frigid winter due to the lack of access to electrical and heating systems. Many tourists visiting Mongolia choose to stay in Mongolian Gers to immerse themselves in Mongolian culture and gain a better understanding of the nomadic way of life. Tourists may think it is a novel mix of urban landscape and nomadic culture, but fail to see the struggles of city migrants hidden inside those felt tents. This touristic perception fails to represent the environmental injustice through the crowded city edge. Gers contain the memories of herders’ nomadic lives, representing the identity embedded in their culture that is now fading away due to the impact of industrialization, capitalism, and global market objectives.

Image 02: Aerial View of Ger District. Source: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, and the GIS User Community.

the case of Urban Migration

What is the reason behind this large-scale migration to capital? What is making nomads give up their herding lives? The climate crisis they face is one of the primary reasons behind it. If we define the ideal habitat as productive soil for agriculture or abundant natural resources, the natural environment of Mongolia challenges this notion. Due to disastrous winters and overwhelming amounts of snow and ice, nature is now challenging the way land has traditionally been inhabited.For example, Dzud which now experiences a large meager amount of arable land. At the same time, it gave local residents a grassland situated in the center of the nation, surrounded by desert in the south and mountains in the north. This abundant “oasis” raises the opportunity to develop nomadic pastoralism. The Mongols realized how precious this opportunity was. Mongolia is one of the earliest nations that have realized the importance of environmental projection and ecological awareness. Even in the Yehe Zasag, also known as the Great Law of the Mongols, the very first legal code developed in Mongolia in the 13th century, the Mongol ancestors constituted a series of ordinances to protect the balance between humans and the environment. Such as, releasing cubs and female animals if captured during hunting activities, protecting water sources, forbidding digging holes in grassland, etc. For millennia, the Mongols had been carefully maintaining the relationship between humans and the environment. However, this balance was broken once rapid industrialization hit this region. The global economy found the “true treasure” underneath this land: mining resources. The International Monetary Fund has recognized Mongolia as one of the resource-rich developing countries, which can receive funds from them to fully develop the potential of natural resources in the countries.[2] The mining industry has become Mongolia’s one of main economic sectors. Nevertheless, mineral exploitation came with a price, a price that needs to be paid by all the humans and non-humans living on that territory or beyond. The grassland and water resources traditionally supported for herding are now used for excavation and mining processes. The oasis is replaced by the mining pit and desert.

Video: Great Timelapser. Oyu Tolgoi Mine Time Lapse: 2020-2022.

Reflection on the urban transformation

From self-sufficient herding nomadic tribes to an urban landscape based on the mining economy, we call this process “developing”. The land is carved up by mining machinery, roads that are built for trucks to transport the resources to the world, and cities consistently growing to carry the mission of a “livable” region. This development has failed to respond to the environmental injustices caused: severely polluted air, minimal water resources, and people who are carving for jobs and houses. Ruined land from mining activities can no longer support food resources for local people. Air full of dust causes large-scale lung disease among children and leads to severe public health conditions. Instead of herding on grassland, nowadays, the majority of the Mongols are working in mining factories, carving the land with excavators, going under the mining pits through hanging ropes to carry out soils which may have the rare materials they are looking for, using the valuable and scarce water to wash out dirt in order to find shining gold. Instead of re-establishing their Gers from place to place, they drill holes to reach deep into the underground, build transport drifts and loading crosscuts to bring minerals to the ground, and develop roads to transport mining productions to the world. Instead of “the grass bends low, the cattle and sheep, to show”, the sky is gray and yellow, mining pits are connected with trucking routes.

When the sky is no longer blue,

When the grassland no longer has cattle and sheep,

When the Gers are settled at the edge of cities,

Will the Mongols sing the dirge of this nomadic land?

bibliography

[1] The home and life of Mongolian nomadic herders (World Wildlife Fund) https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/the-home-and-life-of-mongolian-nomadic-herders

[2] Managing Natural Resource Wealth Thematic Fund (IMF) https://www.imf.org/en/Capacity-Development/trust-fund/MNRW-TTF

[3] Darima Darbalaeva, Anna Mikheeva, and Yulia Zhamyanova. The socio-economic consequences of the desertification processes in Mongolia. (E3S Web of Conferences, 2020),164, 11001. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016411001.

[4] Caldieron, J. M. (2013). Ger Districts in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: Housing and Living Condition Surveys. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 4(2), Article 2.

[5] Mongolia: On the Verge of a Mineral Miracle. (2022, February 11). Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/mongolia-on-the-verge-of-a-mineral-miracle/

[6] Great Timelapser (Director). (2022, October 30). Oyu Tolgoi Mine Time Lapse.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G__0m9V-0l0